Research

Microbial communities are complex due to the multitude of species and diverse types of interactions between them. My research delves into the complex world of microbial communities, utilizing a variety of computational approaches from computational biology, physics, math, ecology, epidemiology, and machine learning. Here are some highlights:

Predicting Fecal Metabolomic Profiles Using Ecological Models with Trophic Levels

A mechanistic model for the gut microbiome to understand fecal metabolomic profiles?

Following the idea of trophic level in macroecology, we designed a trophic model that considers the sequential nutrient consumption and byproduct generation upon consumption. Using a manually-curated database of metabolite-microbe interactions (i.e. consumption or production), our model with four trophic levels generates fecal metabolomic profiles in the best agreement with the real data. Then we wonder if we can improve the prediction performance by adding new interactions or removing existing interactions in mechanistic models. To demonstrate this, we developed the ecology-based method GutCP (Gut Cross-feeding Predictor) that leverages the Monte Carlo algorithm to probabilistically search for interactions to add or remove and demonstrated on the trophic model.

Deep Learning for Personalized Metabolomic Predictions

Accurate prediction of fecal and blood metabolomic profiles based on individual factors?

Many machine learning methods have been developed to predict fecal and blood metabolomic profiles based on microbiome compositions. However, the current state-of-the-art deep learning methods have not been leveraged. In a new study, we proposed a new method — mNODE (Metabolomic profile predictor using Neural Ordinary Differential Equations), based on the state-of-the-art deep neural network models “Neural Ordinary Differential Equations”. Our mNODE outperforms existing methods in predicting the metabolomic profiles on both synthetic data and real data such as human gut microbiomes and other natural microbiomes. Further, in the case of human gut microbiomes, mNODE can naturally incorporate dietary information to further enhance the prediction of metabolomic profiles. Finally, we revealed that mNODE can reveal microbe-metabolite interactions.

Later, we took a deeper investigation into how dietary intervention influences metabolomic profiles via the modulation of gut microbiota. Due to highly personalized biological and lifestyle characteristics, different individuals may have different metabolic responses to specific foods and nutrients. We developed a new method McMLP (Metabolic response predictor using coupled Multilayer Perceptrons) to accurately predict the metabolic responses after dietary interventions of avocado, walnut, almond, broccoli, etc. Beyond the superior performance of McMLP, we performed a sensitivity analysis to generate the tripartite food-microbe-metabolite interactions, which may inform us of their relationships in a data-driven way.

Using Multi-Omics Data to Uncover Ecological Mechanisms

Can multi-omics data be leveraged to decipher ecological mechanisms?

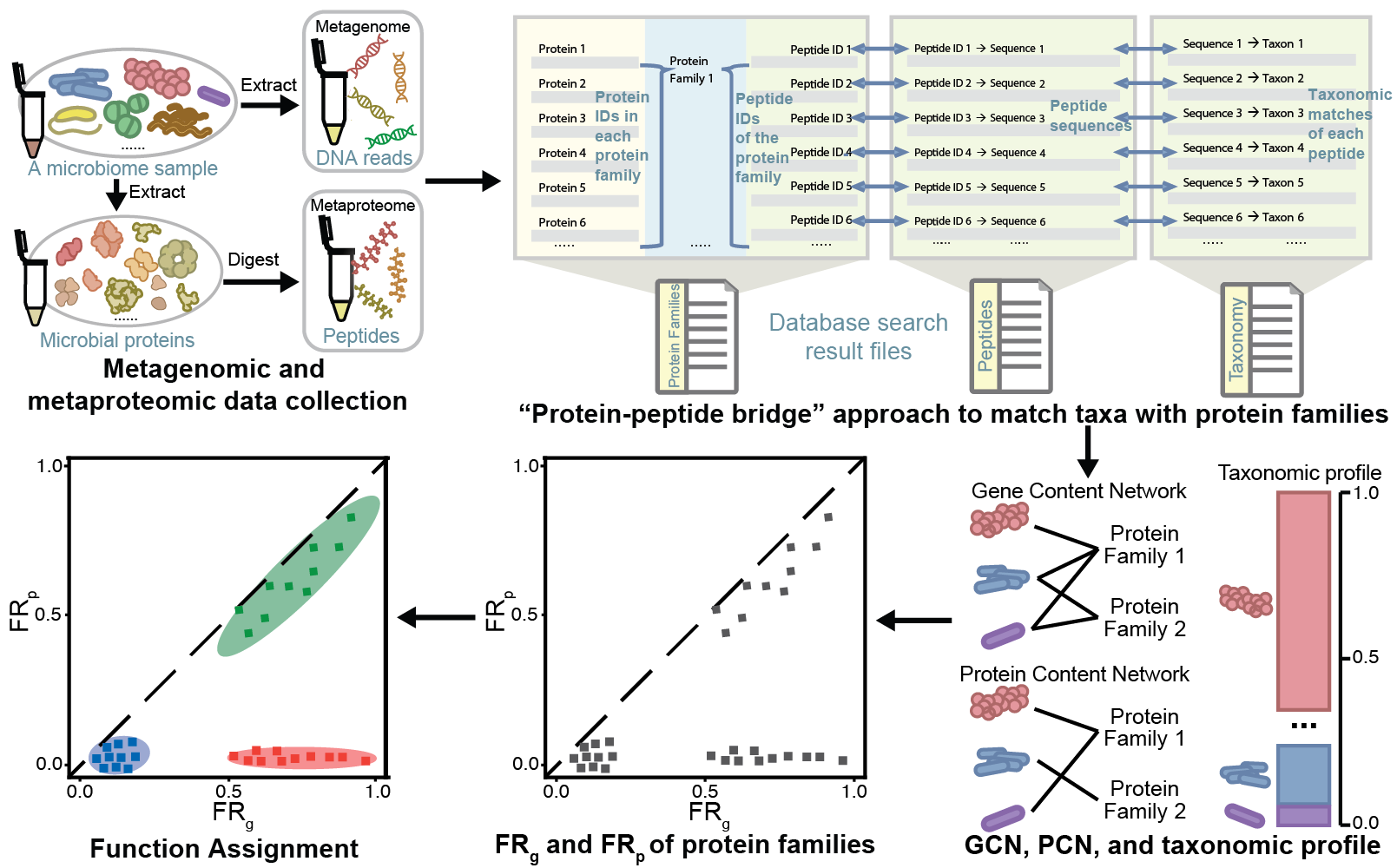

Although many types of experimental measurements such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and metaproteomics have been widely adopted, their potential for unraveling ecological mechanisms underlying microbial communities has not been fully exploited. In response, I proposed a novel ecology-relevant metric, metaproteome-level functional redundancy (FR), which quantifies the extent to which one or multiple functions are covered by many microbial species. This metric enables us to discern differences between healthy and diseased individuals. Based on this metric, I also compared metaproteome-level FR with metagenome-level FR to assign the metabolic or ecological role of each function. The effectiveness and reliability of this approach have been confirmed through its application across diverse microbiome datasets from multiple environments.

Dynamics of Viruses Infecting Chemotactic Bacteria

How do phages infect moving bacteria?

In the past, studies of phage infection in space focused on how phages attack non-motile bacteria. How do phages infect chemotactic bacteria? To study this question, Derek Ping, an undergraduate student from the lab of Prof. Seppe Kuehn, performed experiments by inoculating the chemotactic E. coli cells together with their phage P1vir at the center of an agar plate with a rich medium (see the YouTube video). In the YouTube video, the outermost bright rings are dense bacterial populations that are migrating at about half a centimeter per hour. However, at the center of the colony, there is a darkened area, about 6cm in diameter, which he showed resulted from the collapse of the bacterial population due to phage lysis. Further, at the center of the colony, we observed a dense region due to the rise of resistant bacteria.

We sought to understand how the phage could create the large central region of the colony where the bacterial population had collapsed. Existing theories based on studies with non-motile bacteria showed that phage could not move over such large distances (centimeters) in such short periods of time (hours) without being actively transported. Therefore, we speculated that the phages travel along with migrating bacteria either during the latent period of infection or while attached to the cell prior to injection. To test this hypothesis, I built a mathematical model that included the ability of phages to “hitchhike” with migrating bacteria. The model confirmed our hypothesis, providing a new perspective on phage-bacterial interactions within moving bacterial colonies.

Other Research Endeavors

Besides, I studied the ecological and evolutionary dynamics influenced by interactions within microbial communities:

- Ecological models of microbial exchange of essential nutrients

- Models of microbial cross-feeding at an intermediate scale mediated by carbon sources like acetate and amino acids

- CRISPR-induced arms-race co-evolution between bacteria and viruses: network structure, regime shift, and influence of phage migration

I also worked on COVID-related projects and disease diagnostics:

- Agent-based model for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Data analysis of internal COVID case data for operational purposes

- Prediction of asthma status based on infants’ multi-omics data

This body of work underscores the integration of ecological theory, multi-omics data, experimental biology, and computational methods to address some of the most pressing questions in microbial ecology and human health.